Numismatists often argue about the greatest coin designers in American history. Adolph A. Weinman and Augustus Saint-Gaudens are frequently cited for their iconic coin designs, which have been revived for modern bullion and collector coins. However, when measuring influence and greatness, particularly in terms of an artist’s design for a classic 20th-century circulation coin being reissued for modern coin programs and minted in the tens of millions or more for both bullion and numismatic purposes, a third individual emerges as equally deserving of recognition.

James Earle Fraser, designer of the Buffalo Nickel, stands out as a notable figure in coin design. His design goes beyond the scope of Weinman and Saint-Gaudens, whose designs were adapted only for the obverse of the American Silver Eagle and American Gold Eagle, whereas Fraser’s design was featured on both sides of the American Gold Buffalo issued since 2006 in bullion and Proof and Reverse Proof versions for collectors.

Fraser’s design also appears on the very popular 2001 American Buffalo Silver Dollar, a coin issued to commemorate the National Museum of the American Indian that sold out of its entire 500,000 mintage in ten days that year, something that has not happened since with any commemorative silver dollar even over a more extended period, and the coin remains very popular today.

Like Weinman and Saint-Gaudens, Fraser was a renowned sculptor, studying at some of the same institutions as the other two, and even worked with Saint-Gaudens. His monumental sculptures, like those of Weinman, graced some of the major monuments in Washington, DC.

As far as his most well-known numismatic design, the Buffalo Nickel, differs slightly from the work of Saint-Gaudens and other notable artists because it did not feature an image of Lady Liberty, which was inspired by Greco-Roman art. Instead, the design was purely American, with the obverse bearing the first motif of a Native American on a U.S. coin that was not of a Caucasian wearing Indian war bonnets or a headdress like earlier gold coins and the Indian Head Cent.

While an accurate Native American had appeared on the 1899 $5 Silver Certificate, one had not appeared on U.S. coinage before. The authenticity of Fraser’s Indian is a large part of its appeal to many Americans.

Like Saint-Gaudens, Fraser believed that our coinage had a purpose beyond its role in commerce and should be of high artistic quality, which would positively influence the artistic taste of the American people.

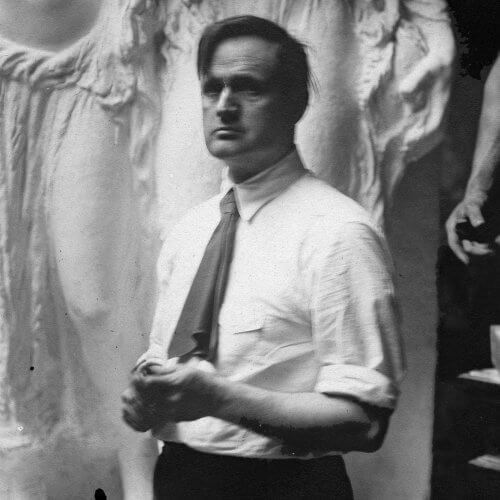

Sculpture Background

Fraser was born in 1876 in Winona, Minnesota, and like many people who would later become great artists, he had a talent for it from an early age, carving three-dimensional figures out of limestone from a quarry near his childhood home. Because of his career as a railroad engineer, Fraser’s father moved his family to the Dakota territory. This pivotal moment in Fraser’s life would later influence his art and coin designs. It was here where an appreciation for frontier life was instilled in the young sculptor, experiencing firsthand the plight of Native Americans in the United States, who were confined to reservations, as well as the thinning of buffalo herds out west.

In 1890, he began studying at the Art Institute of Chicago at the age of 15, where he later began work on what would become and remain perhaps his most well-known sculpture, the End of the Trail, which he completed in his twenties, depicting an exhausted Native warrior riding his weary steed. It was exhibited at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exhibition. It was so widely admired that it resulted in an invitation to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where many great late 19th and early 20th-century artists attended. When he returned to the U.S., he worked four years with Saint-Gaudens, who considered Fraser his most gifted student.

Fraser then established his own studio in Greenwich Village in New York City in 1902. He began teaching at the New York Art Students League in 1906, where he met Laura Gardin, a student he would later marry in 1913, who worked with him in his studio and would become a legendary sculptor and coin designer herself. In fact, the first time he saw an example of his nickel was when he got married and rode the bus that day, paying with a quarter and receiving one of his nickels in change.

In 1902, Fraser completed his exquisite bas-relief depicting a young child. This display of expert craftsmanship would open the door to numerous significant commissions, including a bust of Theodore Roosevelt for the U.S. Senate Chamber and another of Thomas Jefferson, showcased at the 1904 Saint Louis World’s Fair. His monumental sculptures can also be admired at the Treasury Department building in Washington D.C., Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, and other cities, such as St. Louis. Additionally, a bust of his mentor Saint-Gaudens graces New York University.

He also served as president of the National Sculpture Society from 1925 to 1927, vice president of the American Institute of Arts and Letters from 1926 to 1927, and on the Commission on Fine Arts for many years, which at the time was the only entity besides the leadership of the U.S. Mint and Treasury that reviewed the designs that appeared on American coinage.

Working on the Commission of Fine Arts propelled Fraser’s career in medallic work. Until then, his main medallic work was the 1925 octagonal Norse-American centennial medals in silver and gold. However, working at the Commission of Fine Arts helped him develop connections with the U.S. Mint, leading to projects like the 1926 Oregon Trail Silver Half Dollar he designed with Laura, who created the obverse featuring a Native American man, while he created the reverse depicting a settler wagon.

Supremely American Design

When he heard the Mint was preparing to change the design of the Liberty Nickel—which by 1912 had been used for 25 years and thus could be changed without congressional approval—Fraser told the Mint he was interested in preparing designs and models for the new nickel, which he heard would feature Abraham Lincoln. He expressed interest in a Lincoln design, but the idea lost popularity, especially since the Lincoln Cent had started issuing in 1909.

Instead, a design competition was suggested. However, Fraser disliked the idea and proposed to the Mint that he could create a design with an Indian and a buffalo on the same coin that would be “supremely American” and “singularly appropriate to have on one of our national coins,” as he wrote in a letter from 1911. The models he made to illustrate his design were well received by the Mint.

After some time to modify the design by lowering the relief as the Mint had requested as well as increasing the size of the lettering for the denomination, which appeared below the raised mound on which stands the buffalo, the coins went into production in early 1913. There were, however, concerns that the denomination would wear away quickly, so later in 1913, Chief Engraver Charles Barber recessed the denomination and replaced the mound with a flat plain, creating the Type 2 Buffalo Nickel.

There are various uncertainties and ambiguities about which Indian Chiefs modeled for Fraser’s obverse design for the nickel and about the buffalo on the reverse, which some people say should be called a bison. Fraser’s recollection of the chief’s design varied over time, but he did clarify that it was a composite representation, not of a specific individual, but rather a blend of three prominent chiefs–Two Moons from the Cheyenne tribe, Iron Tail from the Sioux, and John Big Tree from the Kiowa tribe. Although some have claimed they, too, were models for the coin, these three chiefs appear to be the only ones attributed to the design.

As for the reverse, Fraser claimed he had sketched and modeled after a famous bison named Black Diamond from the Bronx Zoo. However, Black Diamond was not at the time found at the Bronx Zoo but instead at the Central Park Zoo. Most likely, Fraser was confused about where he had seen the animal, but further confusion came from the fact that Black Diamond was also the name of a railway train that went to upstate New York and was also used in the New York area for anything rare and exotic.

Fraser received many awards for his outstanding contributions to sculptures and monuments, including a gold medal from the Architectural League in 1925. Although he passed away in 1953, and his legacy endures through his extensive body of work, and his artistic treasures have been carefully preserved with his and his wife’s papers at Syracuse University in New York, the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, and the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum. These archives stand as a testament to his enduring impact on the world of art and American numismatics.